High School Students In The Collegiate Scholars Program Get To Know Robots

On a hot morning in July, a sleepy John Crerar Library starts to rouse as students arrive for Introduction to Robot Programming and Design, a college-level summer course for Chicago Public Schools rising seniors. Since Crerar’s renovation five years ago, the University Library’s sciences collections, housed here since 1984, have shared the building with the Department of Computer Science. Hustling and bustling from September to June, Crerar is several notches quieter now.

On the first floor is the Computer Science Instructional Laboratory, with computer stations and classrooms. The lab doesn’t officially open until 10, the same time that class begins, but early-arriving students cajole a building manager into unlocking the glass doors a few minutes before the hour.

The students have traveled to Crerar from all over the city. They’re Collegiate Scholars, enrolled in a program started by the Office of Community Affairs (now the Office of Civic Engagement) in 2003 to help academically talented, intellectually curious Chicago Public Schools students prepare for and succeed at selective four-year colleges. The Collegiate Scholars Program admits 50 rising sophomores each May. Over the next three years, they take summer courses like this one, many taught by UChicago faculty, and have access to dozens of workshops and activities during the school year—on academic subjects, college exploration and readiness, leadership, community service, and more.

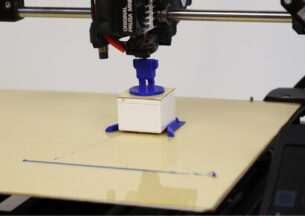

The classroom for this course is organized into a three-by-three grid of tables, each holding a ClicBot robot kit the size of a large shoebox. ClicBot, which retails for about $450, is an educational coding robot. Its modular parts—“brain,” joints, wheels, grasper, and so on—can be clicked together in hundreds of different configurations. ClicBot is the beating—sometimes talking, sometimes rolling—heart of Introduction to Robot Programming and Design, a course with little traditional instruction but much problem-solving in small groups.

The classroom for this course is organized into a three-by-three grid of tables, each holding a ClicBot robot kit the size of a large shoebox. ClicBot, which retails for about $450, is an educational coding robot. Its modular parts—“brain,” joints, wheels, grasper, and so on—can be clicked together in hundreds of different configurations. ClicBot is the beating—sometimes talking, sometimes rolling—heart of Introduction to Robot Programming and Design, a course with little traditional instruction but much problem-solving in small groups.

That hands-on ethic, says instructor Sarah Sebo, is key to what the course wants to give students: their first exposure to programming and robotics plus the confidence, excitement, and sheer fun of seeing a ClicBot do what they programmed it to do. Sebo, an assistant professor of computer science who studies the psychology of human-robot interactions, is one of nine UChicago faculty members teaching Collegiate Scholars this summer. Three doctoral students from Sebo’s lab group are coteaching the course with her.

That hands-on ethic, says instructor Sarah Sebo, is key to what the course wants to give students: their first exposure to programming and robotics plus the confidence, excitement, and sheer fun of seeing a ClicBot do what they programmed it to do. Sebo, an assistant professor of computer science who studies the psychology of human-robot interactions, is one of nine UChicago faculty members teaching Collegiate Scholars this summer. Three doctoral students from Sebo’s lab group are coteaching the course with her.

This Thursday one of them, teaching assistant Alex Wuqi Zhang, in a navy-and-green checked hoodie, sweat shorts, socks, and slides, spends the first few minutes talking the class through a PowerPoint about end-user programming interfaces, a bit of context for the day’s ClicBot programming challenges.

The soon-to-be seniors listening to Zhang have a lot on their minds this summer, says Abel Ochoa, executive director of college readiness and access in the Office of Civic Engagement, who leads the Collegiate Scholars Program. In addition to this class, each student is enrolled in a social sciences course and two college readiness courses: Writing for College and College Countdown. College application deadlines are coming up, and the Collegiate Scholars are honing lists of where to apply, drafting personal statements, and pondering who to ask for recommendation letters—all with the help of Ochoa and his staff.

But for these 90 minutes, the students, in teams of two or three, are fixed squarely on their bright white ClicBots—specifically on programming them to act according to the wishes of another small group they’ve been paired with. The groups have swapped forms indicating how they want the bot to behave: its rolling speed (1–10), whether it makes eye contact (Y/N), and its disposition (empathetic or sarcastic).

At table 1, Scott, Logan, and Anaya decide on a speed of 4. They emphatically reject eye contact (“too freaky”) and just as decisively opt for a sarcastic robot. They hand their form to table 2 behind them and get to work, first constructing their ClicBot according to Zhang’s instructions on a handout. “There we go,” Logan says. “We made a robot.” It looks like a long-tailed dachshund on wheels. “Does anyone want to program it?”

At table 1, Scott, Logan, and Anaya decide on a speed of 4. They emphatically reject eye contact (“too freaky”) and just as decisively opt for a sarcastic robot. They hand their form to table 2 behind them and get to work, first constructing their ClicBot according to Zhang’s instructions on a handout. “There we go,” Logan says. “We made a robot.” It looks like a long-tailed dachshund on wheels. “Does anyone want to program it?”

All three take turns, using tablets and a visual coding language called Blockly, which allows them to drag and drop robot commands. Blockly simplifies their task but still immerses them in programming problems and logic. They’re working through the program when from behind them comes a whir and a voice: “How’s your day, Logan?”

All three take turns, using tablets and a visual coding language called Blockly, which allows them to drag and drop robot commands. Blockly simplifies their task but still immerses them in programming problems and logic. They’re working through the program when from behind them comes a whir and a voice: “How’s your day, Logan?”

All turn in shocked laughter: “You did not make it say that!” Table 2’s ClicBot has rolled toward table 1, stopped, and asked the question with the help of the voice recorder in its “brain.” ClicBot’s brain component also has a light that gives the effect of eyes, and true to table 1’s specifications, this bot is dark—no eye contact desired, none given.

Scott moves the robot to his group’s table for the full demonstration. When it asks about his day, he’s supposed to touch the top of the brain if it’s going well and touch the side if it’s not. At first nothing happens when he touches the top, so he rubs it for a few seconds. The ClicBot responds with a sad sound—the sarcastic opposite of what you’d expect. The day’s challenge met, both groups clap. Applause and laughter ripple across the whole room as robots wheel around and interact with their delighted users.

Programming challenges like this one occupy the course’s first four weeks. In the last two weeks, the established groups team up on a final project: programming a ClicBot, in any way they choose, to address a societal problem. Several groups program their bots to check in on their users’ mental health—an issue that’s front and center for the high schoolers and their friends. One group makes theirs perform as a guide dog for the visually impaired, sensing obstacles and alerting the user. On presentation day it doesn’t work flawlessly, but the ambition and execution are still impressive.

For those students who go on to pursue a STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) education in college next fall, Introduction to Robot Programming and Design will give them valuable experience. For those who go another way, Sebo believes, their ClicBot experience still stands to pay off. “We’ll only have more artificial intelligence systems and robots in our lives moving forward,” she says. “AI can seem scary or unknown.” Having “even a tiny taste” of how robots really work will better equip the students to be informed citizens of that future world.

Behind Collegiate Scholars

Collegiate Scholars was launched in part as a response to studies by the University’s Consortium on Chicago School Research showing that many Chicago Public Schools students were not applying to colleges that matched their ability and potential. The program aims to build confidence and ambition, and has had striking results. For the Class of 2023, all Collegiate Scholars who completed the program were admitted to a four-year college or university; 57 percent were admitted to highly selective institutions, including Stanford, Yale, and UChicago. The scholars collectively were granted $7.1 million in financial aid.

Students apply to be Collegiate Scholars during their freshman year of high school. On average, 300 students complete applications for each year’s 50 available spots. Admitted students “have begun to demonstrate academic curiosity,” Ochoa says; they are typically in the top 15 to 20 percent of their classes but can do better with the resources the program offers, including college-level courses like Sebo’s.

The program looks for students who are underrepresented, which can mean any of several things: no parent or guardian has a four-year college degree; students come from a single-parent household; their background is Latino or African American; or they come from a low-income household.

Some Collegiate Scholars don’t fit those criteria, Ochoa adds, “because another value that we try to provide students with is diversity”—the opportunity to be with students from backgrounds different from their own.