UChicago Research Tests Whether Robots or Humans Are Better Game Partners

You are a detective, tasked with solving a kidnapping mystery based on clues provided in dossiers. Your partner is Agent Lee, who provides information, hints, and encouragement to help you crack the case. The twist? Depending on when you play the game, Agent Lee might be a human, or might be a robot. Which would you trust more?

This question of human-robot interaction was probed in a recent paper by students Ting-Han Lin and Spencer Ng with UChicago CS Assistant Professor Sarah Sebo, presented at the 2022 IEEE Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN) conference in Naples, Italy. Inspired by interactive amusement park animatronics and escape rooms, Lin and Ng designed a playful experiment to test people’s preferences for human versus robot game guides.

“The entertainment industry is moving towards a trend where there’s increasing levels of personalization,” said Ng, a BS/MS student in computer science. “The main problem is, if you have these highly personalized experiences requiring human actors, you can’t have a lot of people experience that without having high costs. Our research focuses on how we’re able to use robots as effective alternatives, and whether people want to interact with robots in this capacity in the first place.”

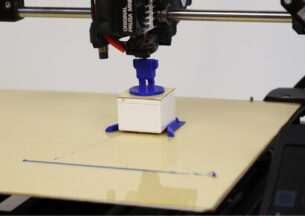

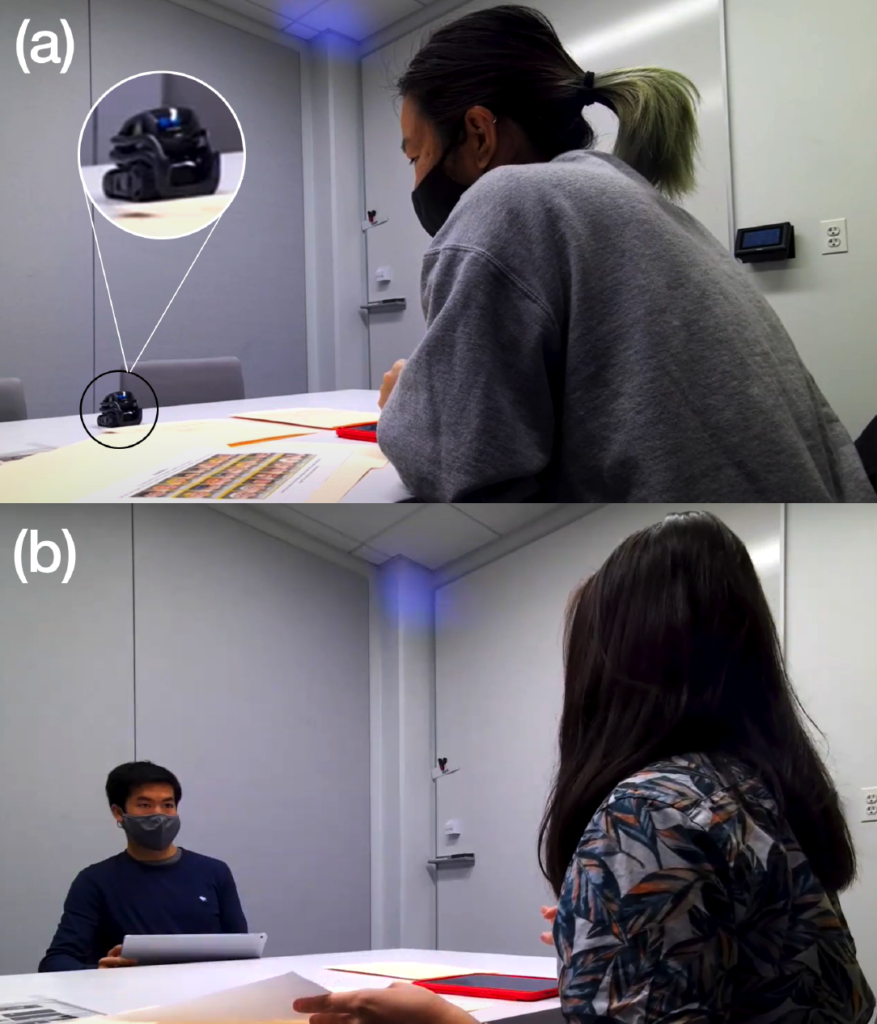

The project grew from Sebo’s Topics in Human-Robot Interaction course, where Lin and Ng designed the initial experiments for the study. In each session, volunteers solved three puzzles loosely based on the board game “Guess Who?” and the codebreaking tasks from escape room experiences. Half the players were accompanied by Ng, who answered their questions and offered hints. The other players worked with a small Vector robot, which Ng controlled from another room remotely in a “Wizard of Oz paradigm” used in attractions at Disney World and other amusement parks.

“The idea of this game is to help people become more familiar with interacting with a robot and have it respond to you, because it’s not something that people are used to,” said Lin, who graduated in June. “The robot is acting as a detective character, it’s working alongside you. So it’s a character that’s integrated within the story we’re trying to tell, which is novel to the human-robot interaction space. We’re trying to replicate what might happen in an escape room or a theme park setting.”

After the games, subjects filled out a questionnaire and were interviewed by Lin about their experience. The researchers then compared the results between human sessions and robot sessions in a between-subject comparison.

Overall, the participants who played with the robot guide rated the experience as more fun than those who played with a human companion. Players were also more likely to say they felt “connected” with the robot, that they got to know the robot game guide better, and that it was actively engaged. But in perhaps the most surprising result, more participants felt that the human guide was “judging” them, compared to the robot guide sessions, suggesting less social pressure with the robotic partner.

“I think that people generally find that playing with a robot could be more fun just because it’s novel; people haven’t done it before,” Ng said. “But it is surprising that people feel less judged by a robot compared to a human staring at you, especially in these more intimate one-on-one situations. It might help inform future design principles where you want to create gamified interaction, especially when the robot is playing a mentor role.”

Sebo said that the result has significance beyond games and entertainment, such as for education or training environments where a robot’s lack of judgment could facilitate more engaged learning.

“Whether it’s a kindergartener learning English as a second language or a worker in a factory that’s trying to acquire a new skill, learning from a robot might be more likely to elicit questions,” Sebo said. “If that role was taken by a teacher or a boss, you might not want to ask the question for fear of sounding silly or like you don’t know what you’re talking about. Maybe people would feel more comfortable asking those types of questions of a robot in the learning scenario.”

The study was one of three papers presented at the RO-MAN conference that came out of Sebo’s topics course, taught in Autumn 2021. In one, Alex Mazursky, Madeleine DeVoe, and Sebo studied robot interactions in a health-care setting, finding that humans prefer “instrumental” tasks such as taking a temperature to “affective” touches meant to comfort. Another paper, by Sebo with Keziah Naggita, Elsa Athiley, and Beza Desta, studied parents’ reaction to their children acting aggressively towards robots, smart speakers, and tablets.

“In my class, students do a small human-robot interaction research project, which normally involves a human subjects study of some kind,” Sebo said. “They’ll program the robot to do something and then recruit human subjects to interact with that robot, and then we’ll be able to learn a little bit more about human-robot interaction as a result. These three papers are examples where there was significant promise from what they ran in the class, and then they continued to polish it for a publication.”