Regional Nuclear Conflict Would Trigger Global Food Shortages, Finds UChicago/NASA Postdoc

Inflamed tensions between India and Pakistan over the Kashmir region have raised concerns about the potential for a limited nuclear war between the two countries. But a new study combining climate, agriculture and economic models finds that the repercussions would extend far beyond the region, producing a decade of global cooling and a severe decline in crop production that would compromise global food security.

The study, led by a University of Chicago scientist, is the first to refine simplistic Cold War-era estimates of global climate and agricultural consequences of a nuclear conflict. Its results show how a sudden change in climate would cause severe crop losses, and an interdependent world economy would exacerbate the effect of regional conflict, causing a global crisis.

The scenario exceeds any food system shock seen in modern history, said first author Jonas Jägermeyr, a postdoctoral researcher in UChicago’s Department of Computer Science and NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

“Sudden cooling is actually more harmful to global crop production than the same amount of anthropogenic warming,” Jägermeyr said. “It primarily hits the northern breadbasket regions, while basically happening overnight compared to a gradual, long-term, systemic climate change where societies have potential for adaptation. In this case, cooling happens within a year, and we don't have the capacity to roll out new varieties of crops to adapt to a changed environment.”

The study, published March 16 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, simulated the worldwide indirect consequences from the use of nuclear weapons and the release of massive amounts of fire-related soot into the Earth’s atmosphere. With an estimate of 5 million tons of soot entering the stratosphere and blocking sunlight, climate models predict an average worldwide decline in temperature of 1.8 Celsius degrees and an 8% drop in precipitation. This sudden climate change would take 10 to 15 years to return to normal, the authors found. This period of cooling would also only delay, not undo, climate change; after a decade, global warming would surge again.

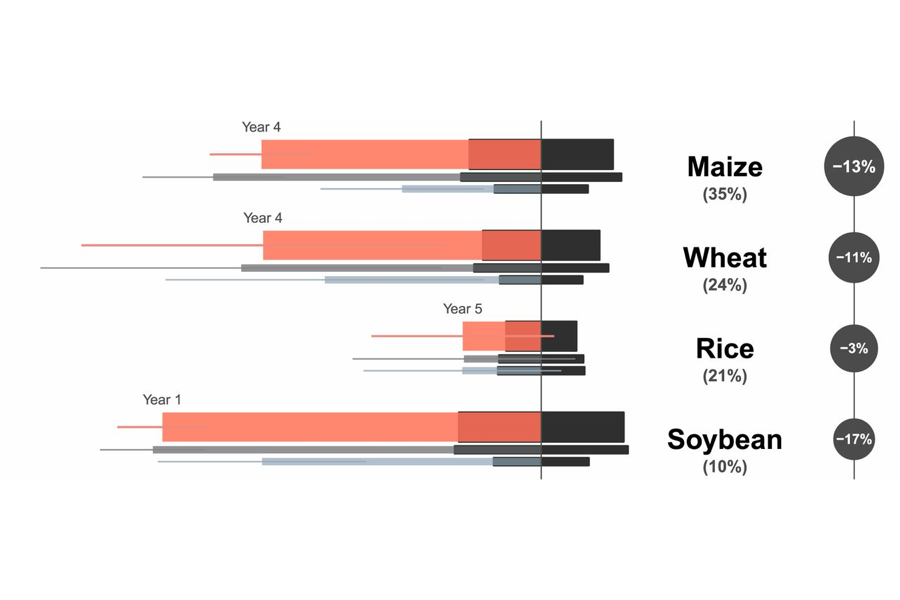

That abrupt cooling would wreak havoc on global agriculture, models showed. Maize, wheat, soybeans and rice—the world’s staple food crops—all show significant declines, with maize and wheat yields both decreasing by over 10% for the first five years. The agricultural impact is most severe in high-latitude regions such as the United States, Europe, China and Russia, causing an alarming “multiple breadbasket failure.” There, lower temperatures would mean plants struggle to reach maturity before fall frost events begin, causing widespread crop failure, the authors reported.

“The impact is very stark,” Jägermeyr said. “It would be the largest anomaly ever recorded, larger than the Dust Bowl event in the ‘30s and exceeding the impact from the largest volcanic eruptions in modern history.”

In order to simulate how these agricultural losses would affect global food security, the study added in models of economic trade. While food reserves would absorb some of the impact of crop shortages in the short term, sustained losses eventually deplete these stores and reduce export of food to countries in the “Global South” reliant upon trade to feed their population. By year four after the nuclear conflict, 132 of 153 countries — a total population of 5 billion people — would experience food shortages above 10%, the study found.

With such a foreboding projection, the study could inspire further nuclear mitigation at a time of expiring treaties and heightened military spending. In contrast to the global nuclear war scenarios studied in the 20th century, the research emphasizes that even a localized exchange of nuclear weapons could be catastrophic for people around the world.

“As horrible as the direct effects of nuclear weapons would be, more people could die outside the target areas due to famine, simply because of indirect climatic effects,” said co-author Alan Robock at Rutgers University. “Nuclear proliferation continues, and there is a de facto nuclear arms race in South Asia. Investigating the global impacts of a nuclear war is therefore—unfortunately—not at all a Cold War issue.”

Other UChicago co-authors include Ian Foster, the Arthur Holly Compton Distinguished Service Professor in the Department of Computer Science; James Franke, a graduate student in the Department of Geophysical Sciences; and Joshua Elliott, a fellow of the Computation Institute.

Citation: “A regional nuclear conflict would compromise global food security,” Jägermeyr et al, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, March 16, 2020. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1919049117

Funding: Open Philanthropy Project and the Center for Robust Decision-making on Climate and Energy Policy (RDCEP)at UChicago.