Head’s Up: UChicago CS Grad Student Designs Device That Directs User’s Head

In pursuit of more immersive technology, scientists and engineers have developed ever more realistic graphics, wearable devices, and forms of sensory feedback. The Human-Computer Integration Lab, directed by Assistant Professor Pedro Lopes, has explored many different ways of using electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) to control a user’s body, enhancing the realism of virtual and augmented reality and creating new interfaces for controlling tech – and allowing tech to control us. The group’s inventions have found new ways of manipulating arms, hands, and fingers, but one important body part has eluded their control: the head.

By controlling head movement, a device can direct its user’s point of view, create realistic sensations of motion, and create new control mechanisms based around simple gestures such as a nod or a head shake. But head orientation is controlled by a complex network of neck muscles, a tricky system to manipulate through electrodes placed on the skin. Previous devices designed to move the head have used a bulky headgear apparatus that is both expensive and restrictive.

In a paper presented at the 2022 CHI conference, PhD student Yudai Tanaka discovered a more elegant solution which he calls “electrical head actuation” (EHA), opening up new opportunities for applications that manipulate the head orientation. Tanaka’s interactive demo for the project, which used VR and his EHA to simulate the G-forces of a roller coaster ride, received the People’s Choice Best Demo Award at the conference, one of the most prestigious in human-computer interaction.

“I was interested in not just actuating the limbs, but in how we can use these actuation techniques to guide a user’s point of view, or what they are looking at,” Tanaka said. “The dominant organs that decide our point of view are the eyes. But it’s very difficult to directly move the eye muscles, because they are beneath our skull. Instead, if you can actuate the user’s head, it might be possible to also redirect where the user is looking. That was the starting point.”

But first, Tanaka needed to figure out how to stimulate the right muscles to produce reliable head motion in different directions. The neck contains a layered system of 12 main and 6 minor muscles controlling head movement, so finding the precise placement of EMS electrodes required many, many trials. While the laboratory was closed during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Tanaka tested different electrode positions on himself for hours each day, until he found the right combination.

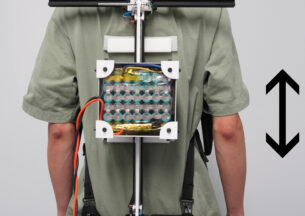

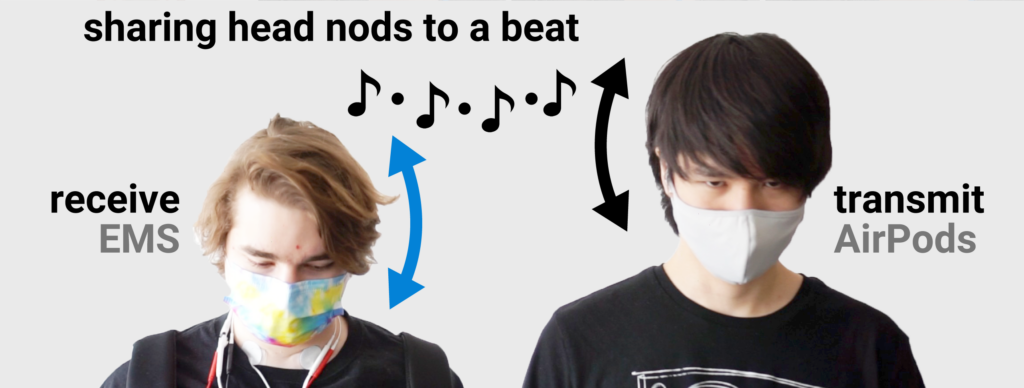

The final setup involves placing five electrodes on the back of the neck and two on the front. The soft electrode pads are unobtrusive and easy to hide – as Tanaka and his co-authors Jun Nishida and Lopes write in the paper, “a simple turtleneck would cover our system’s EMS electrodes entirely.” Once calibrated, the EMS can move the user’s head up and down, left and right, and combinations in between. Tanaka also developed a way to use VR/AR headsets, or even AirPod earbuds as sensors to monitor head position and adjust the strength of the stimulation to create the desired movement.

With the functionality settled, Tanaka set about creating and testing applications that use the system. In one, users take a mixed reality fire safety training course where the head actuator directs their point of view to the location of a fire extinguisher or the emergency exit route. Others include an interface where the user controls the volume on their computer by tilting their head up or down, the creation of realistic sensations of “getting punched” while playing a VR boxing game, and synchronization of head movements between two individuals, which could be also useful for these users to look at the same things at the same time.

“If someone is an expert on a task that uses a large-scale interface, it might be useful to feel how that expert is looking at specific things at specific times through your neck,” Tanaka said.

While the thought of a device intervening in your head movement might be off-putting to some, Tanaka said that the response in user studies and in his conference demos (he’ll bring EHA to SIGGRAPH 2022 this summer as well) has been mostly positive.

“All our electrical muscle stimulation systems have been designed with the goal to assist users while keeping them in control, not removing control,” Tanaka said. “For instance, our systems can detect whether a user moves by themselves or not, and can turn off their assistance when the user is moving against, allowing the user to be in control. In fact, over the last three years, my colleague, Jun and my advisor, Pedro have published five papers on how to measure and preserve the user’s agency during electrical muscle stimulation – it is an area we are really passionate about because we believe that’s the direction of the HCI community: human-computer integration systems.”