UChicago Undergrad Analyzes Machine Learning Models Used By CPD, Uncovers Lack of Transparency About Data Usage

The rise of violence and crime in Chicago has led the city to allocate roughly 65% of its public safety budget to the Chicago Police Department– a hefty 1.9 billion dollars for fiscal year 2023. Millions of that is spent on the upkeep of Strategic Decision Support Centers (SDSC’s): real-time crime centers that use predictive models for surveillance and data collection. CPD, in conjunction with the BJA National Public Safety Partnership and the University of Chicago Crime Lab, conceptualized the expensive SDSC initiative in 2016 to reduce crime in districts, decrease incident response times, increase clearance rates for crime, and improve officer safety. With crime statistics over the last couple years mostly still in the red, justification for the price tag on these types of programs is questionable.

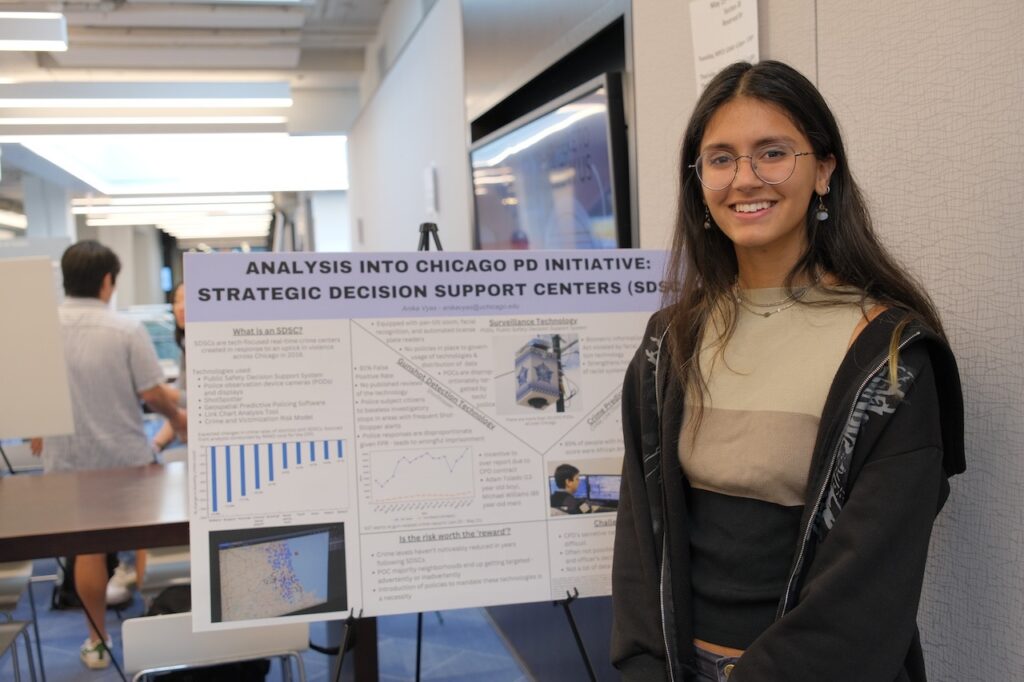

Aside from the expenses it takes to keep the SDSC afloat, a deeper look into the program has raised concerns for fourth-year UChicago student Anika Vyas.

In the spring of 2023, Vyas took Assistant Professor Raul Castro Fernandez’s Ethics, Fairness, Responsibility, and Privacy in Data Science course, which is part of the data science major. The course explored how societal issues affect the data science lifecycle and culminated in a quarter-long research project based on an area of each student’s interest.

“The first message I give students is that to exploit the full potential of technology, and data science in particular, we need to be aware of how these technologies interact with society,” said Fernandez. “The individual project is an opportunity for students to explore socio-technical issues beyond those we see in class.“

When Vyas started reading course material about how AI was used in the justice system, she decided to investigate how that technology was being used closer to home. Her research compiled data from the city of Chicago and the Chicago Police Department, as well as social justice organizations, on the way SDSCs are used for crime prevention and public safety. After looking at the entirety of the data through the lens of Fernandez’s course, she concluded not only was there a lack of transparency surrounding the usage of the tech and data, but also potential for the models to be biased.

SDSCs employ seven core technologies: the Public Safety Decision Support System, police observation device cameras and displays, ShotSpotter, Geospatial Predictive Policing Software, Link Chart Analysis Tool, Crime and Victimization Risk Model Tool, and the SDSC Mobile Application. After testing the technology in six of the districts with the highest rates of violence, Mayor Rahm Emanuel alluded to the program being a success, and by 2019 CPD had expanded the program to all 20 districts.

“Looking into the rate of occurrence of crimes like robbery, burglary and homicide and not seeing the expected levels of decrease was enough reason, in my eyes, to question the models used by the CPD,” Vyas stated.

The surveillance technology used, like the remote controlled PODS that account for upwards of 35,000 cameras across the city, cost more than $60 million a year to stay active. During her research, Vyas found that citizens of Chicago don’t have a say in what information those cameras can collect or how it can be used, and regulation of the data is not clear.

“There don’t seem to be any rules in place regarding footage with no connection to criminal cases,” said Vyas. “For instance, it was shocking to read that CPD had sold Automated License Plate Recognition data to ICE in 2015, which was then used to target and deport immigrant community members. It is a clear violation of privacy and civil rights that puts the entire community at risk.”

Vyas also found that other surveillance technology, like facial recognition software, seem to pose ethical problems because of the type of data used to train the model. In 2020, the CPD entered a two year contract with Clearview, a facial recognition technology company, that would be used for active criminal investigations and was trained using mugshots. With Black people making up the majority of mugshots in CPD’s data, she warned that they could be disproportionately targeted by the software. There aren’t any publicly known restrictions on the use of facial recognition matches either, suggesting that officers can view facial recognition matches without a warrant, probable cause, or reasonable suspicion.

Former mayor Lori Lightfoot and CPD gave questionable responses when it came to the transparency of how facial recognition technology was being used to identify criminals. Both said that Clearview was not being used on real-time or archived videos. On the other hand, CPD also had a contract with DataWorks Plus that specifically used real-time face-tracking software. The contradiction most likely means that CPD was spending money on a technology they weren’t using or they were using it without disclosure.

Former mayor Lori Lightfoot and CPD gave questionable responses when it came to the transparency of how facial recognition technology was being used to identify criminals. Both said that Clearview was not being used on real-time or archived videos. On the other hand, CPD also had a contract with DataWorks Plus that specifically used real-time face-tracking software. The contradiction most likely means that CPD was spending money on a technology they weren’t using or they were using it without disclosure.

Data pulled surrounding ShotSpotter, a popular gunshot detection system used by the SDSCs, showed differing stories as well. An analysis done by The Office of Inspector General of Chicago found that only 9.1% of CPD responses to the 50,176 ShotSpotter alerts between January 2020 and May 2021 showed evidence of a gun-related crime. Northwestern University’s MacArthur Justice Center also conducted a study and found similar results. However, when Vyas used the Freedom of Information Act to obtain data from an internal performance review of ShotSpotter, it was reported that ShotSpotter had a 97% accuracy rate and only a 0.5% false positive rate– with zero false positive results reported during January and May of 2021.

“It was surprising to see the vast difference in the accuracy rate reported by ShotSpotter themselves and the CPD, especially when putting into context the CPD’s continued contract with them,” recalled Vyas. “The fact that this model is being used for law enforcement means that any discrepancies should not be overlooked.“

The implications of ShotSpotter inaccurately dispatching police to districts with the highest Black and Latinx populations have been detrimental. Vyas referenced a class action lawsuit that was filed after 65 year old Michael Williams was jailed for eleven months based on intentional and improper use of ShotSpotter data as evidence. In the complaint, it was confirmed that ShotSpotter had a high false positive rate, but it also declared that CPD had been misusing ShotSpotter alerts to make illegal stops and arrests and detain thousands of innocent citizens near the location of the alert.

“Despite the reports, Chicago still maintains its $9 million a year contract with ShotSpotter,” said Vyas. “By monetizing the use of this technology, ShotSpotter arguably has the incentive to over-report the number of alerts, like it did in the performance review. The contract requirement only mentions being held accountable for gunshots that are missed or mislocated. False alerts would help ShotSpotter meet the performance requirements in hopes of extending the contract another year.”

Vyas concluded in her report that each of the technologies had several potential inbuilt biases and weren’t doing much to support the decrease of crime in Chicago, despite political figures saying otherwise. She emphasized the need for transparency in order to assess the degree to which these technologies are biased or flawed. Unfortunately that type of transparency does not exist right now. Overall she just hopes her research will help others be more aware.

“I hope people read it and learn something they didn’t already know. It’s always beneficial to know when something is going wrong, especially if it’s in your own city.”